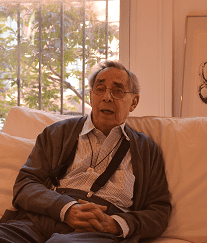

In Conversation with a Pioneer: Dr. Jack Geiger

Today community health centers serve 27 million patients at 10,000 sites across the country — all based on a concept that Dr. Jack Geiger created in the 1960s in rural Mississippi.

Today community health centers serve 27 million patients at 10,000 sites across the country — all based on a concept that Dr. Jack Geiger created in the 1960s in rural Mississippi.

At the Founders Reception on November 16, PCDC saluted Dr. Geiger for his pioneering work and lifelong insistence that health care is a basic human right.

During a recent conversation with PCDC CEO Louise Cohen (right), he reflected on an extraordinary career spanning nearly seven decades. Excerpts from the conversation follow.

The seminal event for me was really in 1957, the beginning of my senior year in medical school at Case Western. That’s when the Rockefeller Foundation gave me a scholarship to work and study for four months in South Africa, which is where the modern community health center was invented by Sidney and Emily Kark (below).

I scrambled to do everything I could to find time to take that scholarship and go. The experience there was the determining one for me in terms of how it shaped so much of my professional career and work.

I scrambled to do everything I could to find time to take that scholarship and go. The experience there was the determining one for me in terms of how it shaped so much of my professional career and work.

I worked at their tribal health center in the so-called Zulu tribal reserve of about 14,000 people, and then I worked at a Zulu public housing project in a place at the end of Durban called Lamontville.

Sidney and Emily had by that point created 45 community health centers in South Africa — not that big a country — that served rural and urban Africans; Indians, or people descended from the indentured servants who’d been brought over from India to work the sugar cane fields in Natal Province; and some poor white communities, both English-speaking and Afrikaans-speaking.

Sidney and Emily had by that point created 45 community health centers in South Africa — not that big a country — that served rural and urban Africans; Indians, or people descended from the indentured servants who’d been brought over from India to work the sugar cane fields in Natal Province; and some poor white communities, both English-speaking and Afrikaans-speaking.

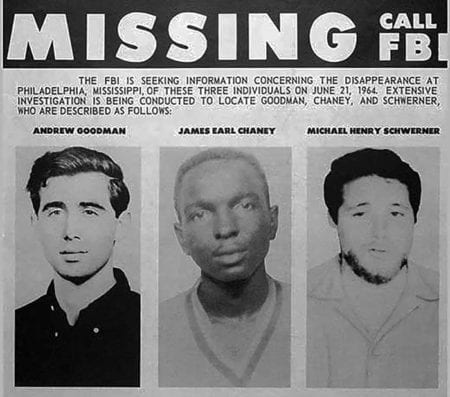

In the spring of 1964, about 30 of us — physicians from across the country, in anticipation of Freedom Summer — had formed an organization called the Medical Committee for Human Rights to go to Mississippi and provide medical care support for the indigenous civil rights workers.

In the spring of 1964, about 30 of us — physicians from across the country, in anticipation of Freedom Summer — had formed an organization called the Medical Committee for Human Rights to go to Mississippi and provide medical care support for the indigenous civil rights workers.

It became a mechanism for bringing many hundreds of physicians, dentists, nurses, social workers, health educators, and others to Mississippi that summer to fan out around the state and provide care and medical presence. However, after the Freedom Summer murders (above) it was clear that protection was necessary and important.

The Epiphany

In December 1964, following Freedom Summer, the Delta Ministry of the National Council of Churches sponsored a meeting of all of us who were left over to discuss what to do next. At that moment — I don’t know what took me so long — for the first time I remembered Lamontville, and Pholela, and the other communities in South Africa, and the root discipline of community-oriented primary care. We all ran around the room chipping in ideas and suggestion and enthusiasm. But it was all just a pipe dream — there was no specific plan of implementation.

One of my partners who I had recruited for the field in Mississippi during Freedom Summer was a man named Count Gibson, who was the head of what was then called the Department of Preventive Medicine. Much later on, Susan Reverby, the historian of Tuskegee, discovered in an archive of the University of Pittsburgh that Count Gibson was one of the first people to write a letter vigorously complaining about the Tuskegee syphilis experiments.

Count and I were flying back to Boston — I was [working] at Harvard, he was at Tufts. We got grounded in Atlanta because of fog and had to rent a motel room. Count said, “If you can get the money, Tufts will sponsor [this health center concept].”

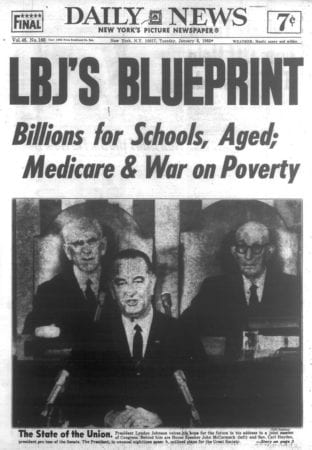

We had a contact at the War on Poverty, this brand new agency called the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO). In January I went down to see their director of research and development, Sanford Kravitz. At that point OEO had no mandate for health care, but you can do a lot of things under the rubric of “research and development.”

We had a contact at the War on Poverty, this brand new agency called the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO). In January I went down to see their director of research and development, Sanford Kravitz. At that point OEO had no mandate for health care, but you can do a lot of things under the rubric of “research and development.”

They were just starting to get data back from Head Start and the Job Corps about the appalling situation of minorities — mostly African Americans — in terms of infant mortality, five-year mortality, infectious disease, TB, and all the rest.

I spent about two hours with him, filling pages of a yellow pad with what a CHC was and what community-oriented primary care was. At the end of that meeting, he said, “How much money are you asking for?”

I had a moment of academic sidestep and jitters and said, “Well, how about $30,000 for a feasibility study of creating a community health center in the United States?”

He said, “You can’t have it. No.”

I asked why not.

“Because you have to take $300,000 and do it now.”

Everybody needs to hear something like that once in a lifetime at least.

Count Gibson and I went back to Boston — we had no idea of what a budget would really cost. First we looked at the law that created OEO, which was an enormously helpful thing to do in a situation like that. We knew that all of the South — the Southern governors, their Senators, and the rest of their medical care establishment — would furiously resist any intervention from outside.

In the legislative debate creating the War on Poverty, they had insisted on the condition that any Southern governor could veto any OEO project in his or her state. And while Sergeant Shriver, the head of OEO, could overcome or override the veto — since the budget of OEO had to be renewed in the Congress every year — he couldn’t spend that much political capital overriding it all.

In the legislative debate creating the War on Poverty, they had insisted on the condition that any Southern governor could veto any OEO project in his or her state. And while Sergeant Shriver, the head of OEO, could overcome or override the veto — since the budget of OEO had to be renewed in the Congress every year — he couldn’t spend that much political capital overriding it all.

This was in effect their barrier to maintaining the existing system of total control of minority populations with regard to health, certainly voter registration, and all the rest.

But then the Southern states decided that if [schools such as] Ole Miss and the University of Alabama could tap into some of that OEO money, then [a Southern state] could get access too. So they agreed to a stipulation that grants to institutions of higher education be exempt from veto, so that Ole Miss and others could profit.

It had never occurred to anybody — certainly not to them, probably not to OEO — that a grant could be made to an institution of higher ed in Boston to do something in Mississippi. We just reinvented carpetbagging, in effect. And while that was by no means the end to a real ongoing resistance, it meant they couldn’t simply stop it, and nobody had anticipated that opening.

Count and I didn’t know what a real budget looked like, and we also realized that this intervention would have two predictable responses: one, furious opposition from the power structure in Mississippi, but equally furious demand from people in poverty in Boston about what we were doing 1,500 miles away while there was nothing on their doorstep.

And so we calculated a budget for two health centers: one in Boston, the other in Mississippi. We didn’t say “Mississippi” when I wrote the whole grant proposals and budget, because we didn’t want it to fly right into the direct face of Mississippi opposition.

Instead the budget and proposal called for two health centers: one in what we called “a Southern rural state” so that no individual state was ever mentioned — in fact, for as long as we could we kept a copy of that grant literally out of [Mississippi] — and the other for the Columbia Point housing project in Boston, which was 8,000 or so people in one low-rise CHC. The initial draft budget for the two of them was something like $1.5 million, which got cut to $1.2 million.

What we had done, I realized at some point, was replicate [the South Africa dynamic]: southern and rural. I’d had my eye on Mississippi from the very beginning. It wasn’t only because we had been there already, but because I had some real sense of the existing power structure and the way things worked under white control.

My feeling was that if we had chosen a site in Georgia, everyone would have thought about Atlanta, and believed that things weren’t as bad as they really were — whereas if we went to Mississippi, everybody would believe it was as bad or worse than existing data showed.

Sergeant Shriver and OEO were very nervous about all this politically, but decided to go ahead. It’s worth noting that, in rapid succession, really in response to the Head Start and Job Corps and other data, they decided to fund multiple projects across the country, such as Rush Medical School and the Miles Square community of the black South Side of Chicago.

The idea was to pick academic medical centers and university medical schools as guarantees of quality, status, and reliability in all those places. That was to change subsequently, and ultimately one of the important forms of change was PCDC, and Ronda and David Kotelchuck, and other people who were in on those important efforts from the very beginning.

We started, and two remarkable things happened. First of all, at the academic medical centers, it must be noted how eager the students were to take part in this work — to volunteer, to bring themselves forward to say, This is the reason I went to medical school, and this is what I want to take part in. The second thing was the number of African Americans, Southern-born originally, whose families had migrated to the North years before.

The OEO law is of interest and relevance to PCDC. Congress, in its wisdom, prohibited any money being spent on bricks and mortar — and wisely, because they didn’t want this funding all poured into buildings. They wanted real service. It turned out that you could renovate, however.

I submitted our grant in February 1964 and it took till June to be approved. Only then did I let a copy of the grant arrive in Mississippi. It was on the governor’s desk the next day.

My job in those early years was twofold. One was recruiting all over the country. The people who were in Denver, Watts, the South Bronx, and Chicago, already occupied with building and planning their health centers — some of them, including African Americans like John Hatch, were themselves recruited to the Mississippi project. But a lot of the work was advertising, speaking, lecturing about CHCs and community-oriented primary care (COPC) in hopes of recruitment.

Secondly, I was keeping the wolves from our door, because instantly the Southern governors, senators, and medical societies at every level had screamed, “This is all socialized medicine,” “This is foreign invasion by Communists,” “It’s a front for voter registration and civil rights work,” and whatever. All of the Mississippi press was of course opposed and covered all of that.

Meanwhile, at the same time, we had the problem of finding a site that would be amenable to renovation, and of picking an area that would be safe. We knew we had an integrated crew and would be vulnerable to attack.

So much of this work, not only in the Delta but also in Boston in a different way, depended on good community organizers and African American leadership in the community — some of whom didn’t act in the best interests of the people. There were elites that saw this all simply as instruments to perpetuate their control.

And, in the early years the OEO protocol was that you could have a community health organization which would help you get the grant, but community organization could only be advisory — which created huge conflicts because the community was very quick to recognize that they in fact had no power. They started to struggle for it, because they were only advisory.

A lot depended on whether the existing community elites were in fact really in support of the aims of the whole project, including its efforts to address social determinants of health, their living standards. Or did they see this simply as an opportunity to extend their own control as members of an elite status.

Really, not a lot has been written about social class conflict within minority communities, of which that response was a manifestation.

It took immense effort, a prolonged effort — the better part of two years, in towns of 10,000 to 12,000 people — to have genuinely community-oriented organizations, which vary greatly in their priorities.

The Prescription is…

The Prescription is…We wrote prescriptions for food — I had that iconic exchange with first the Mississippi governor, who accused us of communism. Then with OEO, who sent someone down to scream at me when I was giving away food and charging it to the pharmacy.

I said, “What’s wrong with that?”

He said, “The pharmacy is for drugs and the treatment of disease.”

And I said, “The last time I looked in my medical textbook, the most effective therapy for malnutrition is food.”

And he went away.

Looking back, the most important and effective thing we did was educational — creating pathways for people to institutions of higher education, first at Tufts and then at Stony Brook. There is an ongoing pathway to Brown University and to the University of Wisconsin. And so many of the African American high school science teachers became medical students, which is of course what they’d always wanted, but needed to means and pathways to do.

Sometimes small things make a difference, even within the personal medical health care framework. Ted Kennedy came to Columbia Point at the beginning of his making health care his central issue.

I took him to the prenatal and postnatal infant care clinic and he discovered that we didn’t have rows of plastic chairs. We had bought big wooden rocking chairs so that women could nurse their babies.

He asked me to meet for dinner that night, and we drafted the outline of the first bill that he introduced that created an Office of Health Affairs within OEO, legitimizing the grants to CHCs and I think added the first $50 million for it. His cosponsor — both then and in the annual renewals — was Senator Orrin Hatch.

Where Hatch will be is not clear to me in this current health care crisis.